- Home

- Gian Bordin

Chiara – Revenge and Triumph Page 2

Chiara – Revenge and Triumph Read online

Page 2

After the prayers, my father took both my hands into his. "Chiara," he spoke solemnly, "you will soon be seventeen and the time has come to think of your future. I have neglected it far too long, because I could not bear the thought of losing you, now that we can no longer hope that your brother will ever return. So today I have placed my seal on the act of betrothal between you and Niccolo Sanguanero. The marriage will be celebrated in July."

A gasp must have escaped my mouth, because my father looked at me sternly.

"Niccolo is a fine young man," he continued, "and you will join a highly respected and successful Sienese merchant family with a long line of famous ancestors, with houses in both Siena and Pisa. You will not want for anything ever, and I hope you will bear him several sons to continue his blood line, since mine has been severed."

I finally found my voice. "Please, father, not Niccolo. Let me be married to a son of da Campo. Then I can remain here with you."

"How could that be? The wife always goes to the house of the husband."

"One of the younger da Campo sons might be willing to live here. Oh father, please."

"A marriage to Casa da Campo would lower your status. I could not allow that."

"But it would not if he became the master of Castello Nisporto after your death." I did not dare to add that I cared little about status.

"The contract has been signed. I cannot go back on my word."

"But why Niccolo? I cannot stand him. He is stupid, and I am afraid of his father. And I thought that you did not like them either."

"I may have made a disparaging remark once or twice about how they like to boast, but that is a minor point. I am an old man, Chiara. I have seen the passing of more springs than most men, and it is my solemn duty to make sure that your future is secure before I hope to join the soul of your mother — a time, God willing, that must be close now."

I continued pleading with him until he chided me severely — the first and only time I can recall — and sent me to my bedchamber to reflect on the proper behavior of a dutiful daughter. He even blamed himself for not having taken another wife who would have provided me with a role model and prepared me for my duties in marriage.

The future suddenly loomed dark and bleak. I could not picture myself as the wife of Niccolo, a man for whom I had no respect, in fact, a man I despised and despised more with every passing moment. Bear his sons? Being touched by him sent a shudder down my spine. That marriage, it must not be. I must try to convince my father of his wrong. There were still almost three months until July. I was certain that my father, whom I had always adored, would not wish his only daughter to be unhappy for the rest of her life. With that I dried my tears and hope returned.

But my father stood firm. He said that it was important for the two families to be united. All my pleading and tears were to no avail. Gone were the days when we would happily ride out together. No parties of chess anymore in the evenings. We hardly spoke to each other. I knew that he was unhappy too and I began to resent the heavy-handed way he had disposed of my future without the slightest regard for my wishes, as if I were a piece of property. This was not the father I knew, the father who since my brother’s departure had always discussed things with me. What had happened? Why did Casa Sanguanero suddenly show an interest in our family after having shown their disdain for so long? I could hardly be the reason. I saw myself as plain, too tall for a girl and rather flat-chested. No, it must be something else, but what? The thing that readily came to my mind was their barely disguised greed to usurp our possessions in the absence of a male heir, and would a foothold on our island with its own small but adequate harbor not be of great advantage for their seafaring ventures? Had my father not hinted that he suspected them of opportunistic piracy? And what about those old feuds between our two families?

As April turned into May, I was getting more and more despondent. I only knew one thing: that I would never be Niccolo’s wife, no matter what, that I would rather kill myself and suffer eternal purgatory for going against God’s commandments. That punishment seemed unreal and remote compared to the known, undeniable dread of matrimony to Niccolo.

What started as a fleeting thought — flee the island, go to one of the famous cities, Siena, Florence, even Venice — slowly turned into a firm commitment. It surely must be possible for a young woman of good breeding, who could read and write, to find suitable employment there. What that employment could be, I had no idea. My planning was still hazy and embryonic and had not reached that stage yet.

However, to be fair to my father, I would make one last attempt to change his mind. But he only looked at me sadly and said that we all had to bear our burden. I could not see why I had to carry a burden when the future could be so bright and happy for both of us; why I could not stay and care for him when he became frail, although I found it difficult to imagine him frail and in need of care. I still saw him as a strong man, full of vigor and life.

So over the next three weeks I prepared my escape. My plan was to steal a small boat from the fishing village of Nisporto and row it to the mainland. I would only take few things along, a change of clothing, my mother’s jewels which by right belonged to me, and my favorite book of Latin poems with the beautiful illustrations on the margin of the pages. I vacillated long on that because it was my father’s and I knew he cherished it too, but I wanted something that provided a symbolic bond with him, that every time I would hold it in my hands I would be with him, in spirit at least.

On the evening of Friday, the last day of May, after our prayer in front of my mother’s picture, I asked my father to embrace me. His eyes lit up. I guessed he presumed that I had finally reconciled myself with my fate which in some way I had, but not the fate he had charted out for me. That night I put my plan into action.

Ignorant of the ways of the sea, I quickly discovered that I was jumping from the frying pan into the fire. Before I knew it, I found myself all alone adrift in a small boat, leagues and leagues from firm land, at the mercy of the wind and the waves, quickly running out of food and drink, and there was worse to come.

* * *

Chiara’s first reaction was shock when she saw her reflection on the polished silver plate that served as her mirror. Deep brown curls with a reddish tint falling to her shoulders. Her long plaits, what she had considered her best asset, gone. For a short moment she thought it was her brother at the age of twelve or thirteen who was looking back at her. The face had the same chubbiness, the same high forehead, the same high cheekbones, the same dark almond-shaped eyes, only the eyelashes longer and the brows less pronounced, but still almost reaching each other. She disliked seeing her ears, usually cleverly hidden by her hair, stick out like her brother’s. Admittedly, her chin, though strong and with the same dimple, was smaller and her nose more delicate. But she could easily pass for a boy, particularly wearing her brother’s short tunic and his breeches, banded at the knees over a leather-soled hose. Her breasts, bound tightly, were not showing. For once she was glad that they were small.

She placed the brown woollen cloak loosely over her shoulders and tied it in front. It would hide her well in the dark. Then she folded the women’s garments she had selected, a coral-red cotton undergown, a pale-green woollen surcoat, opening to the hips at the side, the former tight fitting, the latter more ample, and a rich girdle, and put them into her canvas travel bag, hiding the little wooden box that contained her mother’s jewels underneath. Next, she stuffed the book down its side and finally placed a full water flask made from a pig’s bladder, and a cloth containing a small loaf of bread and a cut of cured dried meat on top. Finally, she slid her short knife with its intricately carved handle into its sheath attached to the broad leather belt that gathered her tunic just below the waist, dropped a few silver and copper coins into the pouch hanging from the belt, and then slung her bag over the left shoulder.

"I’m ready," she murmured.

She went to the window and scanned the garden below. A half-gr

own moon cast elongated, black shadows. Brutto and Catto, the two bloodhounds, came running, lifting their heads eagerly up to her. She had raised them from puppies. Whenever she was outside, they were at her side. Her knees suddenly felt like jelly, and she held on to the sill. Tears blurred her vision. Could she do this to her father? Never see him again? Would she be able to survive? What had looked so simple and straightforward — granted it entailed unknown hardships that she was willing to suffer — had become heartbreaking and forbidding. It would be so easy to call it off. Should she try once more to make her father change his mind? But it only lasted a moment. No, nothing would shift him.

She climbed onto the sill and eased herself out of the window, reaching for the foothold she knew was three feet below. She blocked out all thoughts of falling, focusing entirely on the mental image of the wall features she had burned into her mind over several days. Holding on to the outside of the sill with her left hand, she wedged the fingers of her right into a crack in the wall and searched with her right foot for the small opening farther down. Her foot slipped off twice before she felt secure enough to lower herself to the new position and shift her hand holds. It felt like eternity before the bushes brushed her legs some twelve feet down and she dared to jump to the soft earth, immediately licked and smothered by the two dogs.

"Quiet," she whispered. Obediently, they desisted, sitting down, eyes on her. She looked up to her room, wishing that it would again be hers, the sanctuary of her girlhood, a girlhood she was leaving behind, that would be lost forever.

Avoiding the pebble path, she skirted along the bushes to the far side of the garden, followed silently by the dogs. "Quiet," she whispered again, hugging each animal briefly, and then pointed to the house, saying "Go." She was sure their sad eyes revealed that they knew she was leaving. "Go," she repeated, pointing once more to the house, and they wandered slowly away.

Before dipping into the narrow tunnel that led to the secret exit, she cast one last glance at the castle that had been her home. She tightened her jaws to suppress her tears and strengthen her resolve. Then she opened the heavy iron gate that she had oiled a few days earlier so that it would not creak. She locked it again from the other side. At the bottom of the dark tunnel she hid the key behind a loose stone at knee level.

Once below the high garden wall, she hurried down the path to Nisporto. A few hundred feet from the first houses, she left the track and skirted the village. When she was above the fishing harbor, she scrambled down the rocky slope to the shore, where a row of boats of various sizes was drawn up unto the sand. Staying just above the water’s edge, she approached cautiously.

As she reached the first boat, the bark of a dog made her freeze. The clamor of dogs would be her undoing. She knew that the fishermen had been nervous lately about sightings of pirates between the island and Corsica. They had been raided a few years earlier, and she had heard of another village on the southern shore, where all able-bodied men, women, and children had been carried away into slavery. But the single warning was not followed by renewed barking. Hidden in the shade of the boat, she let her heartbeat slow itself. She had intended to look for a rowboat in good shape and small enough for her to handle. However, with the threat of a dog raising the alarm, she dared not venture farther along the beach. If she was to get away, she had no choice but to take this first one.

She carefully inspected its outside hull — rather difficult in the deceiving light of the moon. It had no visible holes but was in bad need of a coat of paint. Peering over the edge, she was relieved to see the oar inside. Her mind was made up. She placed her canvas bag on the little bench at the stern, folded her cape and put it there too. The next task was to get the vessel into the water. First, she tried to push it, but it simply dug itself deeper into the sand. Maybe she needed to pull the boat, lifting its front at the same time. Jerking it forward by a hand width at a time, pausing in between and listening for any sounds, she managed to get the boat afloat. It almost tipped when she climbed in. She used the oar as a pole to push it into deeper water. There were no sounds except the peaceful lapping of the water on its side.

Holding the oar, she was suddenly uncertain of what to do. It had always looked so easy when a fisherman propelled a boat forward in a flowing figure-eight motion. She inserted it in its lock at the stern and tried to imitate the movement. The boat only began to rock from side to side, forcing her to stop and steady it again. With eyes closed, she imagined the fisherman’s motion in her mind and then executed the vision she had seen. Opening her eyes she notices that the boat was moving forward slowly. Repeating this a few times, she got the boat going. The problem was that it tended to curve, and she was forced to lift the oar out of the water to correct the direction. It took her more than an hour before she could propel and steer the boat at the same time. By then the village had disappeared behind a small headland and she was already feeling the strain in her arms.

After resting for a while, she resumed her toil, steering a straight course along the coast in its northeasterly direction, while trying to stay a safe distance away from the rocky cliffs where the waves splashed high and subsided in white foam. She had to rest ever more frequently as her arm and shoulder muscles tired. Dawn was breaking when she could see Capo della Vita to her right and was able to guess the outlines of the coast of Tuscany, two and a half leagues away, more than twice the distance she had already covered. Had she not expected that by daylight she would be well away from the island? And there she was already exhausted, her arms and shoulders leaden that she could hardly move them anymore.

How naive she had been to think she could row across the straits. She would never make it. Maybe she should row back to shore and walk home. She was sure her father would forgive her, and if he saw how desperate she was to avoid becoming Niccolo’s wife, to what measures she was willing to go, he might relent. Wasn’t she the jewel of his heart? It was almost a relief to abandon her quest. Only a nagging fear remained that he might refuse.

As she turned the boat toward shore, she noticed that the point of the cape seemed farther away than before. Was it only an illusion, a trick of the mind that made distances seem larger when one knew that every move sent knives into arms and shoulders? No, she was definitely drifting away from the island. Frightened, she began to row with as much strength as she could still muster, but to her dismay it only slowed her drift away from land. She called out frantically for help until she was hoarse and finally sank into the bottom of the boat, sobbing, holding her knees to her chest, rocking back and forth.

Exhaustion must have conquered her in the end. The sun was straight overhead when she woke, thirsty and hungry. A brisk wind was blowing from the southeast and the boat was rocking from side to side. With each wave, spits of water spilled over the side. She turned the boat perpendicular to the waves and it stopped rocking. The coast of Tuscany dipped in and out of the horizon with every wave. To the south she could see the length of Elba, from Volterraio in the east to the top of Monte Capanne in the west. Whenever she crested a wave, the dark coast of Corsica loomed in the distance. Elba looked at least as far away as she remembered seeing it from Piombino, the only time she had visited the coast of Tuscany. To the northwest, she could make out Isola di Capraia. She was alone, no other boat in sight.

She had the urge to relieve herself, but how? Unless she did it into the bottom of the boat, she would have to climb onto the little bench at the stern. Then she realized in consternation that this also implied removing her breeches. She could not simply raise her skirts a bit and crouch.

Thirst and hunger finally got the better of her, and she drank and ate half her supplies, while occasionally steering the boat back in the direction of the waves in the hope that within a day or two she would either be saved by a passing vessel or reach some distant shore. In vain she continued to scan the horizon in all directions for rescue to arrive.

Map of Tuscany

3

Ligurian Sea, early June 1347

I was driven along by the wind and the waves for a day and a night without seeing a living soul. At dawn of the second day I saw the pointed peak of Isola di Capraia a league or two behind to my left. If I had not dozed off sometimes in the middle of the night, I probably could have rowed the boat toward it as I got closer, but by the time I woke the current was too strong for my feeble strength and inexperience. I finished the last of my drink and food, watching the island almost imperceptibly shrink in size.

I wondered why I did not see any other boats. Whenever I had been on top of Volterraio, I had always seen dozens of small fishing boats and even the occasional galley and two- or three-masted lateen vessel. Maybe they were all sheltering from the stiff winds.

How was a feeling? Frightened? Yes. Frantic? No. I had resigned myself. Either God would save me or the sea would be my grave as it had been my brother’s. Once or twice I started to pray, but gave up quickly. Neither God nor the Madonna had responded to my daily prayers when I beseeched them to spare me from Niccolo. And why should they heed the pleas of an obstinate girl. There must be thousands of girls facing the same fate who were appealing to them, and what about all the other women praying for their sick children to get well or for their husbands to return from the sea or from war, not to speak of all the men who prayed to them as well. I felt suddenly small and insignificant. So, I waited and waited. I even stopped scanning the seas for another boat.

By the time I saw the merchantman, a carrack, it was less than a quarter of a league behind and approaching fast, its three lateen sails straining in the wind. I jumped up, shouting with joy, quickly wrapped my cloak around the oar and waved frantically. Maybe God had sent help even without my prayers, and I said a few silent words of thanks.

Chiara – Revenge and Triumph

Chiara – Revenge and Triumph Kidnapped and a Daring Escape

Kidnapped and a Daring Escape Yuen-Mong's Revenge

Yuen-Mong's Revenge Frame-Up

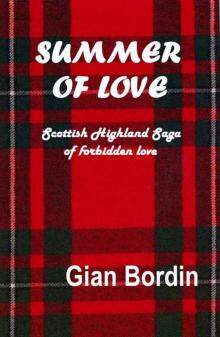

Frame-Up Summer of Love

Summer of Love