- Home

- Gian Bordin

Yuen-Mong's Revenge

Yuen-Mong's Revenge Read online

Gian Bordin

YUEN-MONG’s

REVENGE

Copyright © Gian Bordin 2010

1

Yuen-mong was pleased that Atun stayed out on the wide ledge in front of her cave, taking in the view. She could feel his enjoyment. It promised something for them to share. Every time she stepped out onto this balcony, it filled her with pleasure and contentment. How old is he? she wondered. Having only her parents and herself as a basis for comparison, she could only guess. He was definitely younger than her father when he had been killed at the age of 41, and his mental emanations were also less stable, suggesting a degree of immaturity. She also thought he was older than she, but by how much?

Had she done right, taking him to her cave? … You had to, she told herself. He was so inexperienced and clumsy, he would have perished before the night was over. But would a mate like this really be of much use to her? Would it not just be an additional burden, possibly even endanger her? I can teach him. And he might even be able to help her realize her father’s idea, if his craft was not badly damaged.

That morning had begun like most days. At dawn she was on top of the promontory above her cave, watching the silhouettes of the two night hunters slowly shrink to tiny dots against the golden ring in the dawn sky. As the birds flew out to sea to their offshore rookery, their haunting calls grew fainter. She lost them when they dipped into the twilight below.

Her gaze returned to the ring—a half-circle that dominated the southern skies of Aros, her home world. She fully relaxed into a lotus position, welcoming the gentle breeze brushing her skin like a soft feather. Any moment now. She closed her eyes and raised the flute to her mouth, listening in her mind for the light tingle that heralded the awakening of the dawn bird that nested on the huge broadleaf hugging the rock face below the cave. A flutter touched her. Counting silently ‘one, two, three’, she sounded a high F sharp at the same time as the bird’s challenging warble of A minor – C drifted up to her. The bird’s trilling grew more insistent, as if calling for the dissonance to be resolved. When Yuen-mong slid to a high G the bird shifted to low G – B. Then both paused. The bird again trilled its initial chord, a bit more tentatively, answered by Yuen-mong’s F sharp. They repeated this game once more, when she matched the bird’s call in harmony with a high G. In response, the bird jubilantly launched into its morning melody, while she improvised around it. This was her morning song—a ritual she observed religiously every dawn, weather permitting.

A few other dawn birds picked up the melody, like delayed echoes, creating new harmonies and dissonances. Her mother had told her that it sounded like the carol of church bells on Old Earth when it was still home to humanity more than four hundred standard years past.

She put down her flute and got up, letting her gaze stray over the majestic halo in the sky. Somewhere up there at its outer edge an empty ship was hurtling around Aros ever since before her birth, waiting in vain for its two occupants to return. Dead almost seven years already. She closed her eyes, calling up the loving, serious face of her father, the gentle smile of her mother, who had named her Yuen-mong—Mandarin for ‘complete the dream’ or ‘make the dream come true’—the hope that some day she might take her daughter back to her home world. Then Yuen-mong flowed into a slow dance of t’ai chi, meditating on those images.

When the first rays of the sun caressed her nude body, she stopped, and carefully scanned the horizon all around. No clouds anywhere. The foliage of the ubiquitous broadleaf and silverleaf trees danced rhythmically in the sea breeze. She closed her eyes and listened to the ever-present quivers emanating from everywhere. Just the usual background noise. It heralded a pleasant, warm day. She picked up her flute and climbed down to her dwelling below, a domed cave, about four meters wide and over fifteen long, with a dozen small niches, which she used to store things, and three alcoves, spacious enough for sleeping.

While preparing her breakfast, she softly hummed the song of the dawn bird. ‘Muesli’ was what her mother had named the Spartan meal of the fermented pulp of timoru, a sausage-like fruit, highly poisonous when fresh. Leaching the squashed fruit several days in a lime solution and then fermenting its pulp removed the poison and made a nourishing, but rather bland food, which she used as a basis for most meals. For breakfast she made it more palatable by mixing in nuts and the dried sweetberries that grew on the flat tops of her rock.

She sat on the balcony, slowly chewing the coarse mash, squeezing out every bit of flavor from the sweetberries before swallowing, the way her mother had taught her. While the top above gave an uninterrupted view in all directions, the balcony faced the sunset side and in the morning offered cool shade. She enjoyed looking over the sea, the ever-changing pattern of waves and colors, the golden ring high in the sky like a halo. The slight curvature of its vast horizon was clearly visible. Her father had calculated Aros’ diameter at a mere 8,064 kilometers, small compared to most inhabited worlds.

What will this new day bring? She posed herself this question every morning, knowing full well that each day followed a similar routine of ensuring her survival by gathering food, fuel, and other things to make life more comfortable, but that the moment she left the sanctity of her rock, her very safety depended on constant vigilance and split-second decisions.

Suddenly, a terrible shriek of fear assaulted her, coming from some being up in the sky. Unprepared, her mind had been completely open, and it hit her like a thunderbolt. She dropped her bowl and curled up into a ball, trying to shield herself. It lasted and lasted, but slowly she gained control over her senses, managing to separate her own feelings from those of the other being whose cry of distress resonated in her mind. Its strength and persistence ruled out any birds, even the murderous craw, nor did the fear of death emanating from the savages, the descendants of a failed colonization attempt who had reverted to a stone-age culture, affect her like this. It triggered a vague memory of a similar episode in early childhood. Had they not stumbled a few days later across a small crater reeking of an unknown stench and containing twisted and burned-out pieces of metal which her father had explained were the remains of a spacecraft that had crashed?

As then, the assault ended as suddenly as it had started. Only a flutter remained, throbbing almost imperceptibly. That was different from her previous experience, where the mind had been silenced completely. Did the unlucky soul survive, only to perish with certainty the coming night? She instantly changed her mind about gathering timoru close to her cave, but instead decided to go exploring south from where the flutter seemed to emanate.

A short time later, after having washed herself under the fine splashes of water, which like a shower trickled down from ceiling cracks at the farthest recess in the cave and seeped into cracks in the floor, she dressed in skin-hugging pants and a loose, sleeveless vest from the soft but tough wing skin of a giant craw, she had dyed with the dark brown of the broadleaf bark. Last, she hung a little leather pouch around her neck, dropping it under her top. Her mother had called it an amulet when she had made it for her. At that time it had contained only a gold nugget, shaped in the form of a full-bellied woman. Now the skin of her mother’s preserved thumb tip was inside too. She had made her promise that if she should die, she would preserve it and add it to her amulet, that it might one day be useful to her. She wondered whether the image of removing the skin, blurred by tears, would ever fade, whether that last look at her mother when she said goodbye, leaving her body to the night scavengers, would remain with her for the rest of her life.

After putting on her soft boots, she stood at the edge of the cave balcony, letting her long black hair dry in the breeze before gathering it into a pony tail with her sling, while listening in her mind to any emanatio

ns of life that were not part of the normal background noise. She only sensed the weak flutter from the south. No signs of unwelcome or dangerous intruders, no querulous disturbance of savages. Over her shoulders, she slung her bow and arrows, a carry pack also made of craw skin which contained emergency items and her folded-up craw decoy, and then lowered herself by a rope through the canopy of the broadleaf. The rope dangled from the overhang of her cave to the ground some twenty yards below. She had to jump the last two yards, landing on the soft, humid ground. The end of the rope remained hidden in the foliage. Another quick mental scan that reassured her and she set out at an easy run, staying just within the trees along the sandy beach that swept south in a wide curve. In the low gravity of Aros, she could keep up this pace for hours without tiring. She preferred running to walking, because she was then not bothered by the slight limp caused by a childhood accident.

Gliding noiselessly over the soft ground which was swept clean by the night scavengers, she kept scanning the background for any signs of life that did not blend into the background noise. The weak flutter was still there. Twice she felt the distinct touch of a craw. It was no threat to her as long as she remained under the canopy. That was another reason why she did not run on the beach itself, although she soon would have to cross the open estuary of the Goldnugget River, a sizable water at the southern end of the beach and the craw’s hunting ground. Maybe the predator was after one of the big waders whose constant emanations of fear blended into the background noise. That would keep it occupied.

When she reached the edge of the forest, she spotted the wader zigzagging through the swamp, while the craw came swooping down in hot pursuit. Just when she thought the wader would be swept up in flight by the huge predator, it managed to sidestep its open claws, and the scream of frustration filled the air as the giant barely managed to balance itself where it had come down hard.

Taking advantage of the bird’s temporary immobility, Yuen-mong darted across the open space, carefully keeping to firm ground and jumping over patches of swamp. The wader too had sought safety under the trees at the other side of the estuary. This was her chance to get a juicy roast for her evening meal unless the bird sought refuge too close to the camp of the savages.

* * *

Atun did not remember how long he had remained immobilized in the sponge webbing that kept him pinned in the pilot seat. It was as if he were waiting for something to tell him whether he was still alive or not, whether what he was experiencing was the altered state of being dead — a state he did not believe existed — or simply the utter exhaustion from the bottomless fear he had felt while plunging helplessly toward Aros. No, he was alive. He could actually sense his pulse where the webbing pressed against his neck. What had happened? All he remembered was that shortly after separating from the mother ship and dipping below the outer edge of the ring, the craft had refused to respond to his commands and then this fear, a fear more paralyzing than he thought was possible.

After a few seconds of hesitation, he issued the voice command to release the webbing. Nothing happened. Something was wrong. It took him a few second to know what. The three control and systems status screens only showed horizontal noise. He touched the middle screen. No window appeared. He touched different places. Nothing. Had the AI unit switched off by itself? Was that the reason why he had lost control over the craft? No, the red power light was still on. He repeated the command again, somewhat louder. No response. He tried the command to turn on the screens. Again no change. Not even the light for voice reception blinked.

Straining to reach the override button for the mechanical release, he stretched the webbing a fraction, but not enough. He looked around the cabin of the shuttle. Nothing seemed damaged, except for a few items that had been dislodged and lay scattered on the floor. What miracle had happened that the craft had survived the crash? He tried again to stretch the webbing to reach the release. Damn it! Why did the AI unit have to fail right when he needed it? Concentrating all his strength into his right arm, he was just able to press the button, and the webbing snapped loose.

Freed from his restraint, he did not quite know what to do next. He was still too overwhelmed. Report to the mother ship, but how without voice commands? A vague memory surfaced from one of his earliest navigation drills. Somewhere on the flight console was a communication link independent of the AI unit for just such an emergency. He scanned over the flight console. At its far right was a drawer he had never opened before. He did now. It contained a set of old-fashioned earphones with a microphone mouthpiece. He switched it on and shouted: "KB379, mayday, mayday," repeating it at short intervals three times more. No response, all he could hear was high-pitched static.

"What the heck is going on?" he swore, remembering that he had already failed to hail his ship up near the ring, right after he had lost control.

Not sure whether he could trust his feet, he stood up gingerly and looked out the window. His view was obstructed by tall grasses. He would have to climb on top of the craft to see where he was. Was that safe? Then he noticed that his undergarments felt humid to his skin. Had he wetted himself? He reached inside. There was not doubt, and he could not help laughing. It was a small price to pay for surviving a crash. He should have worn the anti-G pants, but then he had not intended to drop all the way down to the surface.

He removed the offending garments and went to the back of the craft to wipe himself with a disposable hygienic cloth from the dispenser. But even that unit did not want to release its contents. Prying it open, he got out a couple of swipes. After cleaning himself he put on new undergarments and stretch support pants. Then he activated the shuttle door. Nothing happened.

"What’s the matter? Nothing working anymore?" he cried in frustration.

If he wanted to get out, he had to use the emergency ceiling hatch. The mechanism opened easily and he climbed onto the roof of the shuttle. It was sitting in the middle of a vast field of three-yard-high gray grass tufts. The craft had cut a half-kilometer swath through it before it came to rest. A narrow streak of discolored green continued up the slope of the forest canopy all the way to a ridge he estimated to be about a thousand meters higher than the swamp. Its curvature, steep at the top, flattening out at the bottom, provided the perfect setting for a crash landing. He could not believe his luck.

The field was surrounded by forests. Opposite the hill he had skimmed down were some rocky outcrops on a bare hilltop. Behind it, in the far distance, he could discern higher ragged mountain ridges, possibly 2000 meters or even higher. The sun had just risen behind them. From its position on the horizon, he guessed that he had landed on the northern hemisphere of the planet at a latitude between 30 and 45 degrees.

He could not see any living thing, not even insects, but the air tasted sweet and pleasant, a welcome contrast to the recycled air of the craft that always had a hint of disinfectant. He took a few deep breaths, filling his lungs and then emptying them completely, suddenly aware of every cell in his body. It felt good to be alive.

Back inside the craft he was again struck by the stale air and noticed that the recycling unit was silent. If it took him more than a day to get the AI unit back on, he would run out of oxygen unless he kept the hatch open, but would that be safe on this world? He would deal with that problem if or when it came to that. Hopefully he should be able to get the craft ready for liftoff before then. There were still some ten hours of daylight left of the twenty or so hour day on Aros. He switched on his wristunit. Its small holoscreen — a three-dimensional image projected by the unit into a sphere — failed to open. How odd? He would have to be guided by the sun to guess the time or any other data monitored by unit, such as outside and body temperature, heart rate, until he could get the shuttle’s AI unit working again.

Moving the webbing out of the way—it was supposed to retract automatically once the release button had been pushed—he seated himself at the console. He again tried unsuccessfully to get a response to various voice comm

ands. Maybe he had to go back to the bare basics, namely the keyboard hidden under the top of the flight console. When had he last typed on a keyboard? He could not remember.

But, he had no more luck with keyboard commands. They did not even register on the screens. Maybe a vital connection had come loose. He hit the outside of the walls of the flight console firmly several times. Nothing. He tried again. Maybe he should power up the AI unit from scratch. He turned the power off and waited several minutes before turning it on again. The power light duly lit up, and the screens became active, flickered, but the AI unit still refused to respond to any commands. And these devices were supposed to be failure-proof.

Maybe the service manual might help. Without the AI unit, he would have to use the tablet — another gadget from a few hundred years back still used as a backup. But that even refused to turn on.

Hadn’t that old navigation instructor joked about each craft having a paper manual as the final back-up? They had all laughed then. But now this was not funny anymore. Thank God they still included that as part of the equipment. After searching through various drawers, he finally found it behind the panel giving access to the interior of the flight console. He took it out, almost gingerly. It felt strange holding a book in his hands. The last time he had done that was at the Academy of Science, five years back, when one of the professors had arranged a guided tour through the physical scientific library that held remnants of books and journals published four or five hundred years ago.

Over the next two hours, he went through that manual, page by page, studying and trying a score of basic checks and procedures listed under faults. Nothing even provoked a response of the AI unit. He quickly scanned through several of the more advanced maintenance procedures. They all involved dismantling parts of the unit for individual testing and promised to be lengthy affairs that would take him more than a day. It might therefore be prudent to explore first his immediate physical environment, to ensure his safety and, particularly find drinking water and possibly food. With the AI unit not working, he could not even operate the food dispenser or get water, unless he dismantled both units, nor did he know how long the recycled water would be safe to drink or how long the ingredients of the food units would keep without the continuous testing done through the AI unit. The emergency rations in his survival kit would not last more than six days.

Chiara – Revenge and Triumph

Chiara – Revenge and Triumph Kidnapped and a Daring Escape

Kidnapped and a Daring Escape Yuen-Mong's Revenge

Yuen-Mong's Revenge Frame-Up

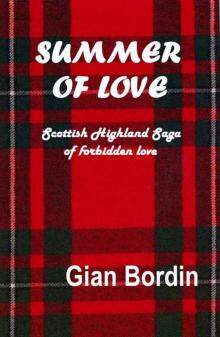

Frame-Up Summer of Love

Summer of Love